Starring: Irfan Atasoy, Sevda Ferda, Yidirim Gencer, Suzan Avci, Reha Yurdakul, Cahit Irgat, Erol Gunaydin, Faruk Panter, Huseyin Zan, Haydar Karaer, Mehmet B. Gungor, Zeki Sezer, Umil Kader, Mete Mert, Feridun Cakar

Director: Yilmaz Atadeniz Writer: Cetin Inanc Cinematographer: Rafet Siriner Producer: Yilmaz Atadeniz

It’s hard to write about these old Turkish superhero movies–especially those directed by Yilmaz Atadeniz–without making reference to the Republic serials of the 1940s. The problem with doing so, however, is that many of you young people out there, with your newfangled transistor radios and souped-up hotrods, will have no idea what the hell I’m talking about. I suppose the appropriately curmudgeonly response to that would be to refuse to continue this review until you’ve educated yourselves on the topic, instead filling space with horrific, Andy Rooney-like ruminations on how butter doesn’t taste the way it used to and why on earth is the print in Reader’s Digest so small until you return with at least one complete viewing of The Perils of Nyoka or some-such under your belts. But, as much as the thought of such an exercise appeals to me, I’m afraid I can’t do so in good conscience.

The fact is that those serials were meant to be seen in a very specific context, a context which simply doesn’t exist anymore. Now, despite what I said previously, I’m actually not old enough myself to have seen them as they were originally presented–i.e in weekly installments as part of a Saturday matinee at the local movie house presented to an audience that I imagine as being made up entirely of young boys in immaculate baseball caps and striped shirts with names like Skip, Biff and Scooter. I did, however, have a vaguely analogous experience of them in that, when I was kid–back in those lean, desperate times when the selection of TV stations barely scraped the double digits–our local “Creature Features” show started featuring old serials as part of their line-up. This meant that every Saturday night, in the middle of a double feature along the lines of Godzilla vs. The Sea Monster and Agent For H.A.R.M., the host, with much ironic fanfare, would present a chapter of King of the Rocket Men, or Flash Gordon, or one of a number of other serials they showed in their entirety over the course of time. This viewing experience provided me with knowledge that allowed me in later years, while viewing the Turkish film Yilmayan Seytan, to remark, “Why, this film is nothing more than a slavish remake of the 1940 Republic serial The Mysterious Doctor Satan!” And, as all you guys out there know, having the kind of knowledge that enables you to let fly with pithy observations like that gets you a whole lot of the you-know-what. You feeling me, ladies?

But the boon that such knowledge was to my budding social life aside, my point is that I was basically able to see these serials as they were meant to be seen: in twenty minute chunks with a week separating them, so that I had enough time to forget just how exactly similar those chunks were before taking in the next one. As such, I was less bothered by how the serials, by nature of their structure and budgetary limitations, were extremely repetitive in their action from chapter to chapter, and depended a lot on expository dialog included to keep people abreast of a story that, for their audience, unfolded over a couple of months’ time. Today most serials that are available for viewing at all can only be seen by way of DVDs which contain them in their entirety. And while it’s still possible to watch them one chapter at a time, having them in such a format, the natural inclination is to watch them in a sitting as you would a regular movie–and if you want to have an experience that rapidly goes from being mildly engaging to tedious beyond all imagining, that is exactly what you should do. So, in short, young people, I’m going to let you slide on this one. In fact, I’m going to go so far as to say that, if you want a taste of what the Republic serials were like, but distilled down to their essence–and with a lot more near nudity and violence–you couldn’t do much better than a Turkish film like Casus Kiran, aka Turkish Spy Smasher.

Now, I say “Republic Serials” not because Republic was the only studio that produced movie serials. It’s just that, while other studios, such as Universal and Columbia, did produce them, they only did so as a sideline to their main business, whereas for Republic they were a primary focus. As such, Republic developed and honed the particulars of making these films to such an extent that they would serve as a model for makers of low budget action films the world over for years to come. The Republic method, first of all, was to recycle, recycle, recycle. Not just costumes and sets, but also story concepts and footage would be handed on from serial to serial, with scripts and action structured to accommodate as much hand-me-down content as possible. Secondly, the hands at Republic knew that the best way to keep things moving at a brisk pace without having to resort to too many costly stunts or special effects was to feature wild fist fights–featuring as many participants as possible–at regular intervals, a practice which became a studio trademark.

One young filmmaker who was paying attention to the lessons that Republic had to teach was Turkish director Yilmaz Atadeniz. In fact, Atadeniz would take his love of American serials and channel it into an entire subgenre within Turkish action cinema. His 1967 film Kilink Istanbul’da–which featured both a masked villain in a skeleton costume and a flying hero called Superman–was one of the earliest entries in a wave of masked hero films that would flood Turkish cinemas throughout the late sixties and into the seventies. These direly low budget features not only built upon Republic’s model by including as many frenetic multi-person brawls as their running time could contain, but also took that studio’s recycling ethos to new heights, borrowing freely not only from each other but from the whole of world cinema, lifting ideas and well-known characters–frequently even actual footage and musical scores–from Western films at will with no regard for copyrights. In Altadeniz’s case, the homage to the American movie serials didn’t stop at a simple appropriation of style, but went on to include actual remakes of them, such as his take on Columbia’s The Phantom, Kizil Maske, and the film we’ll be discussing here today, Casus Kiran, which was a remake of Republic’s 1942 serial Spy Smasher.

Now, I haven’t seen the original Spy Smasher, though I am aware that it’s widely considered to be one of the best of the Republic serials. Being a recovered comic book nerd, however, I am familiar with Spy Smasher himself. The character originated in the pages of Fawcett’s Whiz Comics, which was also the home of the original Captain Marvel before DC Comics sued him out of existence in the fifties (proving that the “D” in their name stood for “Douchebaggery”). When Republic set about bringing the character to the screen, they cast frequent serial star Kane Richmond in the role, and placed at the helm one of their premier directors, William Witney, who had also been responsible for the much lauded Adventures of Captain Marvel the previous year, as well as serial adaptations of Dick Tracy, Zorro and The Lone Ranger. The result proved enduring enough to merit a revival in the sixties and, following the success of the Batman TV series, was edited down to feature length for American TV under the title Spy Smasher Returns.

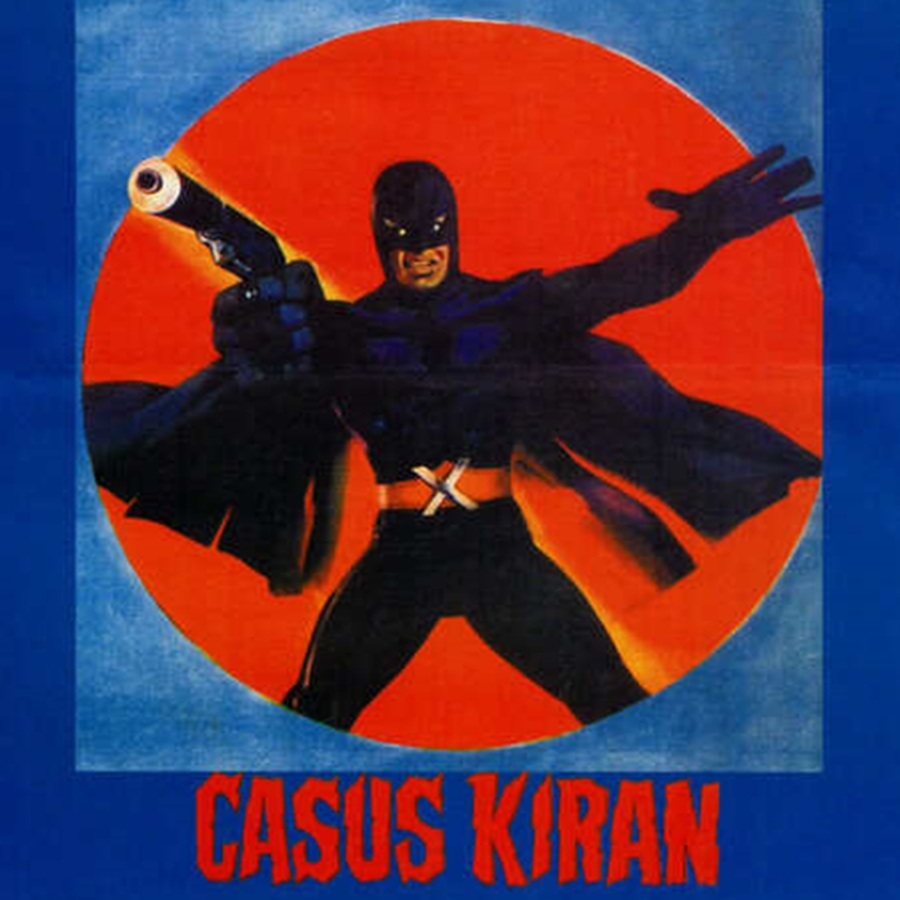

As originally presented, Spy Smasher was a patriotic wartime American hero who did battle against the axis powers. This means that some perhaps less than slight changes would have to be made to adapt him to a 1960s Turkish milieu. One of the most obvious of these in Casus Kiran is that the villains, rather than being Nazis or Japanese saboteurs, are simply rendered as all purpose enemies of Turkey of unknown political bent or national origin. Another change is a result of a certain tendency that these Turkish comic book adaptations have of always making things just a bit more sexy than their source material. As such, Spy Smasher is provided here with a female sidekick/girlfriend in the well-rounded form of Sevda (Sevda Ferda), who accomplishes her end of the spy smashing clad in a black leather tunic and matching knee-high boots. As for Spy Smasher himself, while his comic book incarnation looked like a cross between a superhero and a WWII era fighter pilot, Casus Kiran presents him kitted out in a form-fitting black ensemble complete with cape, Batman-like mask and conspicuously padded chest.

Casus Kiran was made in close proximity to Atadeniz’ first series of Kilink films, and the director brings a lot of familiar faces over from those movies into the main cast here. Star Irfan Atasoy was an exhibitor and distributor who, at the time of Kilink Istanbul’da’s inception, asked that he be given a starring role in the picture, as well as exclusive distribution rights in his territory, in return for providing financial backing. Atadeniz cast him as Kilink’s nemesis Superman and would go on to use him as a hero in a number of subsequent films. Fortunately for all involved, Atasoy, in addition to deep pockets, also possessed the rugged good looks and robust physicality necessary for such roles, as he proves handily in his turn as Spy Smasher. Also present is Kilink himself, Yildirim Gencer, who here plays the masked villain, The Mask, as well as appearing unmasked as “Yildirim”, which is simply The Mask posing as a mild mannered suitor of Sevda’s in order to gain intelligence on Spy Smasher’s operations. Finally we have Suzan Avci reprising her role of “Suzy”, Kilink’s sexy moll–only here she’s “Suzy”, the sexy moll of The Mask’s number two man, The Black Glove (who doesn’t wear a black glove, by the way).

Casus Kiran is a film that is in constant, rapid motion from beginning to end, presenting more of a continuous event than an actual story. One furious fight will lead to a furious chase, which in turn ends in yet another furious fight, and so on. As such, trying to impose the strictures of plot upon it is sort of like trying to identify the conflicts and character arcs within a hurricane or brush fire. Making that task even harder is the fact that, despite no doubt heroic efforts by Onar Films, the existing version is missing large chunks of its running time, with many scenes fading out or simply cutting off before they’re resolved–suggesting in turn that there are other scenes that were probably lost entirely. Despite this, however, I will make my best effort to assign some kind of coherent structure to what I witnessed as I watched the film unfold.

The film begins with a rapid series of scenes showing spies committing various types of mayhem–mostly consisting of blowing stuff up–all over Istanbul. All of these spies are dressed in black with identical hats and skinny ties, which lends sort of an absurd, surrealist air to the proceedings. Over this, a narrator, stating the obvious, notes that spies have become a bit of a problem for Turkey, and then goes on to tell us about a “plucky young man” who, along with his girlfriend, has taken it upon himself to deal with that problem. Soon after that we see Spy Smasher and Sevda in action, roaring in on their motorcycle to the accompaniment of thundering surf music to shoot and punch the black hats into retreat. When the dust clears, the heroes have gotten their hands on a precious tape recording containing the names of all of the spies in Turkey–a tape that will prove to have little consequence at all to the plot, such as it is, of Casus Kiran.

Sevda is the daughter of police Detective Cavit, and she and Spy Smasher use the fruits of their clandestine crime-fighting activities to secretly help him in his investigations. Because of this, everyone thinks that Cavit is buddies with Spy Smasher and knows his real identity, which seems to really annoy him. The fact is he doesn’t know, nor does he know of Sevda’s involvement in Spy Smasher’s activities, yet no one wants to hear it. By the time we meet the old guy, Cavit is so exasperated with this state of affairs that, whenever someone says that he and Spy Smasher must be really tight, what with all of his helping him with his investigations and everything, Cavit just says, basically, “Look, I could tell you I’m not, but you’ll just say that I am anyway, so let’s just drop it”. Beyond the fact that they’re sort of making Sevda’s dad’s life miserable in the course of helping him, another notable thing about Spy Smasher and Sevda is that he calls her “Darling”, while she calls him “Spy Smasher”.

Of course, all of those black hats aren’t just running around blowing stuff up all over Turkey of their own accord. That sort of thing requires management, and what better way to meet the men–and woman–in charge than in a scene in which they slap around some chained women in lingerie. At the top of the organization, as I’ve mentioned before, is the appropriately named The Mask, with the more mysteriously named The Black Glove at his side. Suzy, in her role as moll, seems to mainly keep the home fires burning, but also serves a crucial function by performing some weird musical numbers in the seedy nightclub that rests atop the gang’s headquarters (numbers that sound like traditional Turkish folk music despite Suzy being shown performing in front of a standard issue 1960s pop combo). The Mask and his spy ring’s main activity seems to be counterfeiting, but there are also repeated references to “product” in “bags” that, in combination with the existence of a laboratory and some suggestions of tests done on human guinea pigs, seem to indicate that they are also involved in drug trafficking, though it’s never entirely made clear. At the time of our meeting them, however, what they’re really excited about is that they’ve kidnapped a British scientist whom they hope to use as bait to draw out a rival gang of spies they wish to eliminate. Spy Smasher and Sevda foil this plan, however, by barging in and rescuing the scientist as soon as The Mask’s black hats have finished blowing the rival gang of black hats away.

With this The Mask decides that the gang’s first order of business should be getting rid of Spy Smasher. He, too, has heard that Detective Cavit is cozy with the hero, and so Spy Smasher and Sevda’s efforts to “help” her dad result in him being targeted by a ruthless gang of spies who will stop at nothing to get him to divulge information that he actually doesn’t have. With this begins a series of attempts by the gang to kidnap Detective Cavit, which lead to a series of furious fights, chases, and narrow escapes. Somewhere in all this The Mask starts showing up at the Cavit residence in the guise of Yildirim, Sevda’s suitor. To be honest, you’re not supposed to realize that Yildirim is The Mask, but I don’t feel that telling you counts as a “spoiler”, since trying to maintain an air of mystery around the villain’s identity in a film in which Yildirim Gencer appears is a pretty futile endeavor–much as it would be in a Bollywood movie that featured Amrish Puri or Amjad Khan in the cast. Anyway, knowing that Yildirim is The Mask will make you appreciate all the more the hilarity of one particular scene in which The Mask’s goons invade the Cavit home during one of Yildirim’s visits. When the black hats pressure Sevda to reveal Spy Smasher’s identity, she–apparently weary of Yildirim’s advances–fingers him as Spy Smasher, and the black hats, apparently also unaware that Yildirim is their boss, give him a thorough working over, during which one of the goons tells him that he “looks like a duck” without his mask on.

In addition to each other, Spy Smasher and Sevda also have a constantly muttering comic relief sidekick, Bidik, who performs a number of undercover assignments for them. These invariably seem to result in Bidik bringing back information that leads Spy Smasher and Sevda into a trap, necessitating that they engage in yet more furious fights followed by chases which end in fights. The inclusion of such a sidekick is just one of many similarities that Casus Kiran bears to a slightly later Turkish film, 1969’s Iron Claw the Pirate. This is no real surprise, as Iron Claw was directed by Cetin Inanc, a longtime assistant to Atadeniz who was also the screenwriter of Casus Kiran. Like Casus Kiran, Iron Claw features motorcycle riding boyfriend and girlfriend masked heroes doing battle with a masked villain determined to bring ruin to Turkey–though in the case of Iron Claw that villain was none other than Fantomas. One thing that I think Casus Kiran has over Iron Claw, however, is that, as the female half of the team, Casus Kiran’s Sevda gets a much better shake than Iron Claw’s girl hero Mine, who tended to get sidelined a lot and didn’t seem to play a part in the action equal to that of the male hero. Sevda, on the other hand, despite Spy Smasher’s top billing, gets an equal amount of screen time and plays a comparable part in the action, even coming to Spy Smasher’s rescue on occasion.

As Casus Kiran nears its conclusion, The Mask, finding the entirety of his operation foiled by Spy Smasher, starts to plan his exit from the country. As one last, generous act of silliness, he determines that this move necessitates the casting of the gang’s massive supply of gold “into the mold for armchairs”. The resulting armchairs look like passenger seats from a commercial airliner, which I think may make this an instance of a plot point that is purely salvage-driven. In any case, The Mask’s refusal to travel light proves to be his undoing, and the delay allows Spy Smasher and Sevda to catch up with him, leading to the final furious chase and fistfight.

More than any of the other examples of Turkish pulp cinema I’ve watched, Casus Kiran seemed to have a sort of dreamlike quality. Even after repeated viewings, I still had difficulty maintaining a grasp on its details, as if it had somehow eluded comprehension by way of its combined surreal velocity and faded, ghost-like appearance. A state of hypnosis seemed to set in soon after I pressed “play”, as if I was watching less a movie than a screen saver featuring men in black hats and skinny ties being perpetually hurled back and forth to a soundtrack of pilfered surf music. Given this, I have to marvel anew at what is one of the true wonders of world genre cinema: that an inspiration as prosaic as old American movie serials could result in an experience so strange and almost uniquely un-movie like in its effect as Casus Kiran. Though it’s a movie of many–if perhaps somewhat simple–pleasures, I think that it is this hallucinatory kick that I treasure most of what I took away from it. It just serves to confirm that, as drugs of choice go, mine–meaning. batshit insane movies like Casus Kiran–is a very good choice indeed.

Hi! I simply wished to take the time to create a remark and say I have truly appreciated reading through your blog. Thanks for all your work.